'Shipmate'

Autumn 2015

One of two ships painted in 'dazzle' paint in Liverpool Docks

Taken on trip at last AGM.

Taken on trip at last AGM.

Editors Page

Hello again for another edition.

This one will be a bit shorter than the last ones as I have yet to receive ANY articles for 'print'.

I would like to thank all members who made the trip to the last AGM in Widnes. I'm sure that, like me,

the other 27 enjoyed it.

The North of England isn't too bad and we do have both electric and gas!

Our next one is in Portsmouth on April 1st to the 4th 2016 to be held at the Royal Beach Hotel, Southsea.

Shirley at IoW Travel has the information but I will put it in the 'Flash Signals'.

Another item is the usual one at this time of year - subs! Dennis has asked me to remind all about payment. There is a Direct Debit Form which can be downloaded on the site or I can email one to you if

you contact me via email.

I have been in touch with Peter Edmondson and he still has a good supply of 'slops' to sell - at knock down prices - that you could get for Christmas!!

We were going to send a questionnaire out to all members as to any changes you would like to see. This has been held until all committee members can supply their input and also ask at the next AGM.

I hope to see you at The Royal Beach Hotel in April.

Roger - Editor.

Hello again for another edition.

This one will be a bit shorter than the last ones as I have yet to receive ANY articles for 'print'.

I would like to thank all members who made the trip to the last AGM in Widnes. I'm sure that, like me,

the other 27 enjoyed it.

The North of England isn't too bad and we do have both electric and gas!

Our next one is in Portsmouth on April 1st to the 4th 2016 to be held at the Royal Beach Hotel, Southsea.

Shirley at IoW Travel has the information but I will put it in the 'Flash Signals'.

Another item is the usual one at this time of year - subs! Dennis has asked me to remind all about payment. There is a Direct Debit Form which can be downloaded on the site or I can email one to you if

you contact me via email.

I have been in touch with Peter Edmondson and he still has a good supply of 'slops' to sell - at knock down prices - that you could get for Christmas!!

We were going to send a questionnaire out to all members as to any changes you would like to see. This has been held until all committee members can supply their input and also ask at the next AGM.

I hope to see you at The Royal Beach Hotel in April.

Roger - Editor.

Hms Collingwood History - cont from Spring edition.

THE VISIT OF KING GEORGE VI

His Majesty The King visited the Establishment on 25th July 1940. He was standing on the dias inspecting March Past when the air raid warning sounded. The parade marched off at the double to air raid shelters and Heads of Departments each went to their place of duty shelter. The King had one allotted to him in the Wardroom block. Major De Garnier and I were in the next one. It was a warm sunny day and no-one actually sheltered. It was a lone plane sighted off St. Margaret’s Point and no danger. We walked up and down for about twenty minutes, saw the King depart and then went in to sample his favourite cigarettes laid out with magazines in typical naval thoroughness – every eventuality duly considered. They certainly were an improvement on ticklers!

THE FALL OF FRANCE

June, July, August. The war clouds closed in dark and menacing around our beleaguered Island. Rousing words of Winston Churchill became grim reality. Day after day in June, phrases from his pontifical utterances in the House of Commons came across the radio in the Wardroom and on the Mess Decks.

June 4th. ‘We shall fight on the seas and oceans. We shall defend our Island whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, in the fields, in the streets, on the hills. We shall never surrender.’

June 18th. ‘Let us brace ourselves to our duties and so bear ourselves to our duties and so bear ourselves that men will say ‘This was their finest hour’.

August 20th. ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.’

Stirring stuff!

Life had added a new dimension to this small island. Every city, town, county and district were front line targets from now on. The separation of families by Call Up was one thing but now the stress and anxieties had become two way. We lived in a beleaguered Island. Our homes were in the front lien. We were all in it together. This was an unreal, unnatural hard fact, difficult to take in. Truth and reality were now on opposing sides in our minds. Truths that we were taught to believe in were suspect. What we had gone to war to defend could be blown to smithereens in one night.

Not only so but we were now in a state of siege, expecting invasion and here we were like sitting ducks, with ten thousand young men, weaponless and defenceless, in the first line of the threatened invasion. It was no sinecure. The sense of responsibility in the minds of the training personnel was heightened and could be sensed. The Wardroom had become the Mess and meeting place for high ranked Army types. The red chevrons of high command as ominous as their secretive manner.

We knew that we were hosts to the staff of the Army stationed in the forts along the hill; but strange faces appeared every day and we knew that they were planning the line of defence of the Portsmouth fortifications to the landward side, along the inner ditch of the Napoleonic period. But that was all; until one memorable lunch hour of consternation and hurried consultations dragged us all in. The Invasion was imminent and it had just been discovered on the hill that there was no reservoir of water inside the Hill fort, that it was piped from the outside mains. Drums, receptacles, tanks, anything that could be laid hands upon had to be procured immediately. The conversation became free; assessments of how long position could be held; there were approximately five thousand men with arms but only fifty rounds of ammunition per man, to be deployed at certain strategic positions from the beach, around us to the forts and along the fort line.

I remember going home to my wife and daughter on the ridge most vulnerable. We discussed whether she should remain or catch the morning train to my parents on the Moray Firth. We decided that would be even more vulnerable so she stayed.

We had sailors in tow defence posts on either side of our ridge and on the night, thought vulnerable, I took home two large vats and Navy ration Cocoa. She spent the late evening making hot liquids. At 12 midnight I loaded then into the car and became delivery man. Coincidence is the byword of life.. It happened that the first posted guard to call out ‘Halt! Who goes there?’ spoke in a broad Caithness accent, to which I replied ‘Another dirty Wicker, - what’s your name?’ and an excited voice came back ‘Advance and be recognised –I’m a Swanson from Staxigoe.’ Our morale was on the top of the world. We forgot why we were there. We were back home.

History tells of Hitler’s damp squib. Life went on in HMS Collingwood, an oasis of activity, uninterrupted by the Blitz around us in Portsmouth and Southampton.

In the early days the Roman Catholic personnel were ministered to by Father Frawley, the elderly priest in Fareham, a much loved man in the town. As the numbers grew it became impossible for him to play an active part within the training schedule and he depended upon me to send personnel to the Presbytery when problems arose. He fell into the habit of calling at my home when he visited his folk in the Highlands area of the town and we became great friends. It was natural therefore that when the first RC Chaplain was appointed in 1941 we had a common ground on trust which grew into a strong friendship which has spanned the years. The Revd Gerald Costello belonged to the Redemptorist Order, a quiet deeply spiritual man, highly educated, with a sense of humour that made him a favourite with everybody.

At the suggestion of the Commander, Gerald made his office in the Warrant Officers Wardroom Office and used the dining area as his Chapel and for lectures; I retained the wardroom and the anteroom as the small Chapel for private prayer for all. It was a happy relationship and since we both covered the Establishments in the whole area we were able to keep oversight over one another’s classes when one or other would be called away.

As I have said, life went on in Collingwood uninterrupted by blitz until the fateful night of 18 June 1943 when huts in the Maintop were wrecked by a single bomb. So far as I remember 27 were killed. Except for the RC lads who were buried in their own area and those claimed for burial at home, the Church of England padre and I buried 13 in a column length of graves to be found in the north east corner of Haslar Cemetary. This is the reason why there is one grave in each of thirteen lines. I have made tryst over the years by walking the lines of these and others from the Establishments under my care, during these blitz years.

The chaplaincy duties of writing to relatives and burying in lines of graves was harrowing. These, along with others I had to deal with in other establishments within my area, had their effect upon my attitude to my sense of vocation, in my day-to-day dealings with men and my words to them on Sundays. To put it in a sentence I had matured. I was confirmed that I was where I was needed. In all sincerity what I preached, during these days, I lived and I lived for these chaps who came to us for three short months; batches coming and going every week. It kept life exciting, new faces, new problems new challenges and always its load of sorrows and anxieties to share; never without them. They came from every corner of this beleaguered Island and each day News bulletins told of cities and towns blitzed and always the callers at the Chaplain’s Office. Out of the concern and anxieties, at Sunday Service, we had a tryst prayer until the war ended. Every Sunday at 10.30 Greenwich Mean Time, we would pray for the folks at home, for the Collingwood men at sea on the Seven Oceans, and for each other – always at that hour. It had its rewards.

I had a Captain of an armed merchant cruiser in the Indian Ocean write me for a copy of the prayer ‘Because he had a group of sixteen ex-Collingwood men who insisted that they meet at the given time on the ship’s stern and he had joined them.’

To quote the writer to the Hebrews of his men of faith ‘Time fails me to tell’ – of many more men who through these three years in Collingwood’s history needed their padre in time of crisis.

Preaching was a challenge to my personal faith. The God in Whom I believed was very real for such grave times of crises. I believed in the Universal Fatherhood of God. A God whose ultimate purpose was slowly but surely coming to fulfilment in the Lordship of The Risen Christ over His World, and we were confronted by the forces of evil. The Old Testament was a gold mine in these dark times. I remember the morning I saw our young Scottish architect walking up the road with his plan and his yardstick, I exclaimed ‘There goes a young man to meet an angel’ and there goes my sermon for next Sunday morning. My hard labour in Hebrew at university and college was always paying dividends and this was one of them. The padre who was standing with me, waiting for our classes to appear said that he had missed that story in the Old Testament; but it is there in Zechariah 2 the story of the young man, who met an angel, when he was going through the myrtle groves with his yardstick. ‘Where are you going?’ said the angel. ‘To measure Jerusalem, what is the length thereof and what is the breadth thereof’ and the angel reminded him that he was on the losing end. As if he could measure a city with a yardstick. Of course my young architect could measure and give data of every hut, every store and every mess desk in that huge establishment but when he had said all he had said little or nothing. He had not even begun to measure the Collingwood that we were daily creating. His was only a conglomeration of huts and data. It was the living mass of individual men and women, with their families back home, that made it what it was; the human mass that gave it its existence, the movement of men through its gates, that was to give it its measureless reality ad infinitum over these years and, continued into the second phase of its existence in which I was to share its life and in the years since, the lives of many more who have passed through its gates.

A UNIQUE NICHE IN NAVAL HISTORY

From this point in time forty years on it can be seen that HMS Collingwood has indeed a claim to a place in the watershed of naval history. It saw the end of an era when the Hostilities Only Seaman Entry ended and the Establishment was taken over by the new and developing Electrical Branch, t become the nerve centre of the modern Navy we now know it.

The old ways and methods of naval training in gunnery and navigation, communications and seamanship, came under the impact of modern science. We were already aware of the change in the growing tensions between the West and East sections of the establishment as the grip of the electronics ‘take-over’ invaded the four seamanship areas.

The quarterdeck gunnery classrooms were allocated as Chapels and common rooms for the Catholic and Church of Scotland and Free Churches personnel. This was done to return the Warrant Officers Wardroom to its original use as accommodation for junior officers. Father Costello and I had previous dealings with Mr Morton the Area Dockyard official in charge of properties and he was most helpful; he fitted out our two Chapels to our every wish. I remember it was a source of wonder to the other chaplains when we exchanged the prayer rails we had; his dark teak one for my light oak one; a sensible practical exchange to suit the rest of furnishings and in keeping with my Communion Table.

A week or two after he had settled in his new Chapel Gerald was drafted to Marine Commandos. His classes had come to an end. It was the first break in our very close friendship. We met again for three short hours on the Sunday before D Day. He was sitting in my office at Collingwood waiting for me to come in from church. The General had dropped him there on his way to the final briefing at Southwick House. Gerald was to obtain a radio for the men. The Commandos had moved into canvas in the small hours of the morning, they were in the wood a mile west of Hambledon Bridge. I got him the radio and took him home to lunch. When his time was up I asked him for his location and he had not a clue, he knew vaguely that it was somewhere west. He was lucky that I had been using the roads through the Top Security camp in the recent period when the fall in workload at Collingwood had given me more time for the extension of my oversight and I was able to visit the crews of landing craft in the little havens and rivers of the New Forest sea board. I had been doing this task since their inception, visiting the headquarters of Captain Hughes-Hallet at Cowes on a weekly basis.

I can recall clearly the excited exclamation of recognition as we crossed the bridge at Hambledon when Gerald said ‘I remember that gun post’ and when we entered the woods past the American sentry who knew me, we had hardly gone a mile amongst the hundred of tents when he said ‘Oh! There is my tent’. How he picked it out I shall never know.

That night he went in with the first wave of assault on the beaches opposite Caen. I heard that they had terrible casualties. The next night I was on duty with the assault ships bringing back the wounded. I kept on seeking news of him. On the Friday night I heard that an RC Chaplain, a Commando, was on board badly wounded. I went to see him but it was not Gerald. Three years later we were serving together again in HMS Raleigh and I went with him to meet a new padre who had changed from the Army to the Navy. It was the Commando I had seen badly wounded. He remembered and recognised me. He was Padre Bill Brisco.

Gerald and I served together until his demobilisation and he returned to his work within the Redemptorist Order. In 1952 when I was serving in HMS Daedalus, our RC Chaplain Michael Barry, was taken fatally ill and I was asked by Commodore McCarthy to arrange for their Sunday services. I phoned the Redemptorist House at Streatham, London and got Father Costello to fill in. He came and he lived in our home for three weeks, cementing a friendship that has continued across the years. Strangely enough, when he went and a new chaplain was appointed, it was Bill Brisco who turned up to take the lace of Michael Barry.

To get back to Collingwood. The takeover went on a pace. The Royal Marines had taken over the maintop enclosed shelter and gymnasium for stores and workshops. The foretop became the Marine transport area where Monrad vans were equipped and overhauled on a weekly basis for the shuttle service to the battlefields of Europe. All this had taken place before Admiral Sedgwick had handed over to Captain Benson on 31st August 1944, when the final break with seamanship and gunnery traditions had taken place.

The longboats on their davots, the capstain and chain lockers etc and the large gunnery building fell into disuse, until in 1945 it became the rehabilitation centre for men retaining for discharge to civilian life.

So the bell bottomed Jack gave way to the fore and aft rigged Artificer and lecture rooms began to fill with all the electronic equipment of the new age of technological science. I saw it all happen.

My Collingwood flimsies read like the passing out parade of commanding officers from Sedgwick to Benson to Keble-Wight. It was a period of swift change to which the old hands found it hard to adjust. The old routine gave way to the new the old faces began to disappear from the Wardroom and the CPO’s Messes. Soon Mr Brown and Mr Ward, the Officers of the Watch, the Barrack Master and I were the last of the originals. Every week new faces arrived in the wardroom – HO specialist officers, university graduates and specialists in electronics with the intellectual capacity to master the continually expanding horizons of radar and electronic development. They were men of undoubted ability who had jumped rank because of their specialisation and some of them were lacking in the naval disciplinary requirements of a training establishment. They were a grand lot of fellows. Some of them with all the athletic fervour of overgrown students, which indeed they were. They were still students continuing hard in their studies.

I remember the day the document was passed round the Wardroom offering permanent service in this new Branch which was to become the foundation stone of the modern Navy.

Many signed the roster but there were others whose names were missing from it. They were being pressed to reconsider the opportunity offered. One of them I remember was the son of the Manse in my northland. He was a brilliant student, senior to me in the Honours Mental Philosophy Degree course at Edinburgh University 20 years before. He was a magnificent specimen of a red headed Scot, a Rugby and rowing Blue and as wild and untamed as the Pentland Firth on whose bleak shore he has been born and bred. He was a full-blown Commander ‘Wavy Navy’ but its discipline was not for his untamed spirit. When he left the service he seemed to flit around the civil airfields in England and Scotland. I used to ask about him until I heard he had joined the Dounray Nuclear Establishment, then in its infancy and he was there until he retired in recent years. He was in some kind of responsible personnel post. In a unique way he was continuing in his father’s footsteps, to be responsible for the inhabitants of the parish of Reay for indeed that is where the nuclear station is built. His father had been there for well over 50 years; he ruled with a stern Calvinism and with a broadminded humanity that made him feared and loved. There was a story told in my youth, how the minister of Reay, at the catechising of his parish, was seen at the top of the village street and the good man of the house near the bottom was sent to the village pub to fetch the refreshment. He came home ahead of the minister inebriated. The good wife, so ashamed, pushed him in the box bed and closed doors. The minister arrived and the catechising began. ‘Now’ said the minister, ‘Tell me about Adam’s fall’. The good woman got up, opened the bed doors and called ‘Come out of there Adam, you should be ashamed of yourself, the minister has head all about you’ and of course he had. He was reputed to have a dry sense of humour and would not have passed up such an opportunity.

I am sure it was his peculiarly dry sense of humour passed onto Donald that instigated the scrum attack on the Bomb Blast Safety Wall outside the Wardroom Door, in order to celebrate the fall of Hitler on VE night. After dinner, in full Mess Undress, they formed a formidable scrum, pushed and pushed until they fell on a crumbled heap of bricks. The Commander, who shall be nameless, ‘was not amused’. He shared not their sense of humour. Their leave stopped, messages had to be sent to waiting wives that their men folk would not be home that night or the next maybe, until the unknown culprits appeared before the Commander.

Perhaps it was my extrovert sense of humour that saw the funny side of the whole incident, from the discomfiture of the Executive to the stoppage of leave to ‘Officers and Gentlemen’. Had I not been missing, my fourteen stone would have been press-ganged into such a sublimating expression of sheer freedom of mind and spirit which overcame the whole nation on that memorable night.

This would seem to be a fitting end to the Collingwood wartime story. If I have glossed over the grim reality of war, it is because even now after forty years, it is difficult to write of the many sorrows and grim anxieties that loomed up week after week in the Chaplain’s office. In these early days of war there was no welfare department where the trained visitors do their marvellous work, only the Chaplain. Our telephones were red hot, passing on men’s concern after news of blitz came across the radio. We became adept at tracking up necessary information. In small towns the police never let us down. After 10 years of city crunch experience I knew where to begin in a city. It never failed, to ask to be put through to the Mayor or the Provost, for prompt action. The night of the terrible blitz on Liverpool, when Birkenhead dockyard area was specially mentioned on the News, four young fellows crowded into my office in sore stress, their homes were actually on the dock front. I phoned the Council Offices, gave names and addresses and within minutes the news came. Their homes were completely wrecked but their families were safe in a Church Hall. We had them put on the first train with transport to the ferry within the hour. Just one incident out of many more.

I have used this story because it illustrates the feedback of the work of the Chaplain in peacetime as in war. In 1953 on the dockside at Liverpool, a porter was helping me to get my wife and her baby son and young daughter out of a taxi when a shout came from thirty or forty yards down ‘Leave the Padre to me, come and take over here’. An orange coated porter rushed up, his face beaming and said ‘You don’t remember me Sir but I shall never forget you. You stay here and I will see your wife and family on board and come back for you and the gear’. Three years later we docked at 7.30 in the evening and a porter was standing on the dockside, in his off-duty suit, waving to catch our attention. He was first up the gangway. He had been watching the passenger list for the previous six months, waiting for our return. We were first off the ship at 7am. Our gear was already freed from Customs and the family’s car was standing by for us to get away. He was on standing by for us to get away. He was one of those lads. ‘Cast thy bread on the waters’ so say the Good Book.

I would finish where I began. I have kept two tributes as a fitting conclusion. I make tribute to the Wrens. They were the light and life of every department from the cookhouses and stores to the offices of the executive and the busy hive of the ship’s office. They were not only an adornment they were the backbone of the Establishment. The very atmosphere of it seemed to have got into their system. They were cheerful, willing workers. The messengers who popped in at the office, as regular as the bugle calls, lightened up the days for us. The Pay Office was bossed by the CPO and PO, two Wrens who themselves worked long after hours, nights on end, keeping the thousands of entries up to date. The First Officer, Millicent Fry, was the daughter of the famous CB Fry. She was a young lady of great charm who knew how to weedle and get things done. We saw their numbers grow from the first thirty entries to over nine hundred strong. They were not housed in the Establishment. Between the Training Commander’s Office and the Dental Department, they had a Common Room and Rest Room with small dormitory accommodation for duty staff. Most of them were local girls who lived at home.

The National Childrens Home in Alvestoke was taken over as Wrens’ quarters. I remember the first time my sister-in-law, the PO Pay Wren came home, with her affronted complaint that she had been put in charge of the small children’s wing, where the seating accommodation in the bathroom was not only too near the floor and in a line, but also as Mark Twin once said ‘Exceeding small’.

My last tribute I would begin with the words, ‘The first shall be last and the last first.’

I doubt whether anyone has remembered or indeed known that the first batch to enter the Establishment were not ‘Hostilities only’ but seventeen year old recruits for ‘Seven and Five’ (years). Their ship’s book number began PSSX. They formed a new and select Branch ‘Defence Equipped Merchant Ships’ – The DEMS. They were being trained for a dangerous task. They were at the beginning of the Gunnery Course when I arrived and my first caller at 4.30 on my first Monday in the Establishment was a lad who was utterly miserable and homesick. He had run away from home. He had left a widowed mother with four of a family and the realisations of its consequences had begun to dawn on him. He was shy and introvert and I was at a loss how to deal with him so I took him home. It was a favourite trick of mine; waifs and strays were always to be found there and I knew he would get a warm welcome from my wife and sister-in-law, the Pay Wren.

When we arrived the young Australian Chaplain from HMS Daedalus, the Revd Peter Parker was with them. He had been invited to a farewell dinner he was on draft to HMS Prince of Wales. His name is now amongst their honoured list of dead. It was a slap up dinner to fit the occasion, and the lad was too embarrassed to eat. However, he came back the following week and from then on he became a fixture in our home. The DEMS as they were called were drafted RNB then to Northern Parade School, Portsmouth; from there latterly to Totton. They were the heroes in top mould, climbing on board coastal steamers, tankers, etc their light aircraft gun over their shoulder off the Isle of Wight or Portland or Southampton, to take over the night run through the Straits of Dover. They went through during the dark hours to Southend. There they handed over to the Army for the North Sea stretch, then back on the night run with the southbound convoy. In eighteen months the three hundred and fifty Collingwood Batch dwindled, until there was little more than thirty odd left. ‘Out Willie’ was a survivor three times in the month of May 1941. It was a trauma for a teenager. He went home on 5th May for his first seven days survivors leave. He had lost four of his mates during the night, the ship sinking under him as he and another tried to break open the jammed Bridge door, where two of them were with the Captain. The neighbours, in his Parkhead Glasgow street feted him. He was back within the week on his second survivor’s leave of twelve days and they did not believe him. In his typical Galsgow humour he said they event sent the ‘Bobbie’ to see if he was adrift. He returned and picked up a convoy off Plymouth. That night they were bombed and he was launched into a sea of oil from off a stricken tanker. When he was offered another spell of leave he refused it, telling his story and ending with the remark ‘If I go home this time they’ll chase me down the street’. The Commander at Northern Parade got in touch with me and he was sent home to us.

I think you will agree this is a fitting end to the Collingwood wartime story. I have always thought that these seventeen year olds were the epitome of the silent service to which they were proud to belong, the unsung heroes of the war. They deserve a place in this inadequate tribute. They epitomise the honoured place, HMS Collingwood, the ships company and trainees will always hold in the annals of naval history.

This completes the Rev's history of Collingwood and I thank him.

THE VISIT OF KING GEORGE VI

His Majesty The King visited the Establishment on 25th July 1940. He was standing on the dias inspecting March Past when the air raid warning sounded. The parade marched off at the double to air raid shelters and Heads of Departments each went to their place of duty shelter. The King had one allotted to him in the Wardroom block. Major De Garnier and I were in the next one. It was a warm sunny day and no-one actually sheltered. It was a lone plane sighted off St. Margaret’s Point and no danger. We walked up and down for about twenty minutes, saw the King depart and then went in to sample his favourite cigarettes laid out with magazines in typical naval thoroughness – every eventuality duly considered. They certainly were an improvement on ticklers!

THE FALL OF FRANCE

June, July, August. The war clouds closed in dark and menacing around our beleaguered Island. Rousing words of Winston Churchill became grim reality. Day after day in June, phrases from his pontifical utterances in the House of Commons came across the radio in the Wardroom and on the Mess Decks.

June 4th. ‘We shall fight on the seas and oceans. We shall defend our Island whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, in the fields, in the streets, on the hills. We shall never surrender.’

June 18th. ‘Let us brace ourselves to our duties and so bear ourselves to our duties and so bear ourselves that men will say ‘This was their finest hour’.

August 20th. ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.’

Stirring stuff!

Life had added a new dimension to this small island. Every city, town, county and district were front line targets from now on. The separation of families by Call Up was one thing but now the stress and anxieties had become two way. We lived in a beleaguered Island. Our homes were in the front lien. We were all in it together. This was an unreal, unnatural hard fact, difficult to take in. Truth and reality were now on opposing sides in our minds. Truths that we were taught to believe in were suspect. What we had gone to war to defend could be blown to smithereens in one night.

Not only so but we were now in a state of siege, expecting invasion and here we were like sitting ducks, with ten thousand young men, weaponless and defenceless, in the first line of the threatened invasion. It was no sinecure. The sense of responsibility in the minds of the training personnel was heightened and could be sensed. The Wardroom had become the Mess and meeting place for high ranked Army types. The red chevrons of high command as ominous as their secretive manner.

We knew that we were hosts to the staff of the Army stationed in the forts along the hill; but strange faces appeared every day and we knew that they were planning the line of defence of the Portsmouth fortifications to the landward side, along the inner ditch of the Napoleonic period. But that was all; until one memorable lunch hour of consternation and hurried consultations dragged us all in. The Invasion was imminent and it had just been discovered on the hill that there was no reservoir of water inside the Hill fort, that it was piped from the outside mains. Drums, receptacles, tanks, anything that could be laid hands upon had to be procured immediately. The conversation became free; assessments of how long position could be held; there were approximately five thousand men with arms but only fifty rounds of ammunition per man, to be deployed at certain strategic positions from the beach, around us to the forts and along the fort line.

I remember going home to my wife and daughter on the ridge most vulnerable. We discussed whether she should remain or catch the morning train to my parents on the Moray Firth. We decided that would be even more vulnerable so she stayed.

We had sailors in tow defence posts on either side of our ridge and on the night, thought vulnerable, I took home two large vats and Navy ration Cocoa. She spent the late evening making hot liquids. At 12 midnight I loaded then into the car and became delivery man. Coincidence is the byword of life.. It happened that the first posted guard to call out ‘Halt! Who goes there?’ spoke in a broad Caithness accent, to which I replied ‘Another dirty Wicker, - what’s your name?’ and an excited voice came back ‘Advance and be recognised –I’m a Swanson from Staxigoe.’ Our morale was on the top of the world. We forgot why we were there. We were back home.

History tells of Hitler’s damp squib. Life went on in HMS Collingwood, an oasis of activity, uninterrupted by the Blitz around us in Portsmouth and Southampton.

In the early days the Roman Catholic personnel were ministered to by Father Frawley, the elderly priest in Fareham, a much loved man in the town. As the numbers grew it became impossible for him to play an active part within the training schedule and he depended upon me to send personnel to the Presbytery when problems arose. He fell into the habit of calling at my home when he visited his folk in the Highlands area of the town and we became great friends. It was natural therefore that when the first RC Chaplain was appointed in 1941 we had a common ground on trust which grew into a strong friendship which has spanned the years. The Revd Gerald Costello belonged to the Redemptorist Order, a quiet deeply spiritual man, highly educated, with a sense of humour that made him a favourite with everybody.

At the suggestion of the Commander, Gerald made his office in the Warrant Officers Wardroom Office and used the dining area as his Chapel and for lectures; I retained the wardroom and the anteroom as the small Chapel for private prayer for all. It was a happy relationship and since we both covered the Establishments in the whole area we were able to keep oversight over one another’s classes when one or other would be called away.

As I have said, life went on in Collingwood uninterrupted by blitz until the fateful night of 18 June 1943 when huts in the Maintop were wrecked by a single bomb. So far as I remember 27 were killed. Except for the RC lads who were buried in their own area and those claimed for burial at home, the Church of England padre and I buried 13 in a column length of graves to be found in the north east corner of Haslar Cemetary. This is the reason why there is one grave in each of thirteen lines. I have made tryst over the years by walking the lines of these and others from the Establishments under my care, during these blitz years.

The chaplaincy duties of writing to relatives and burying in lines of graves was harrowing. These, along with others I had to deal with in other establishments within my area, had their effect upon my attitude to my sense of vocation, in my day-to-day dealings with men and my words to them on Sundays. To put it in a sentence I had matured. I was confirmed that I was where I was needed. In all sincerity what I preached, during these days, I lived and I lived for these chaps who came to us for three short months; batches coming and going every week. It kept life exciting, new faces, new problems new challenges and always its load of sorrows and anxieties to share; never without them. They came from every corner of this beleaguered Island and each day News bulletins told of cities and towns blitzed and always the callers at the Chaplain’s Office. Out of the concern and anxieties, at Sunday Service, we had a tryst prayer until the war ended. Every Sunday at 10.30 Greenwich Mean Time, we would pray for the folks at home, for the Collingwood men at sea on the Seven Oceans, and for each other – always at that hour. It had its rewards.

I had a Captain of an armed merchant cruiser in the Indian Ocean write me for a copy of the prayer ‘Because he had a group of sixteen ex-Collingwood men who insisted that they meet at the given time on the ship’s stern and he had joined them.’

To quote the writer to the Hebrews of his men of faith ‘Time fails me to tell’ – of many more men who through these three years in Collingwood’s history needed their padre in time of crisis.

Preaching was a challenge to my personal faith. The God in Whom I believed was very real for such grave times of crises. I believed in the Universal Fatherhood of God. A God whose ultimate purpose was slowly but surely coming to fulfilment in the Lordship of The Risen Christ over His World, and we were confronted by the forces of evil. The Old Testament was a gold mine in these dark times. I remember the morning I saw our young Scottish architect walking up the road with his plan and his yardstick, I exclaimed ‘There goes a young man to meet an angel’ and there goes my sermon for next Sunday morning. My hard labour in Hebrew at university and college was always paying dividends and this was one of them. The padre who was standing with me, waiting for our classes to appear said that he had missed that story in the Old Testament; but it is there in Zechariah 2 the story of the young man, who met an angel, when he was going through the myrtle groves with his yardstick. ‘Where are you going?’ said the angel. ‘To measure Jerusalem, what is the length thereof and what is the breadth thereof’ and the angel reminded him that he was on the losing end. As if he could measure a city with a yardstick. Of course my young architect could measure and give data of every hut, every store and every mess desk in that huge establishment but when he had said all he had said little or nothing. He had not even begun to measure the Collingwood that we were daily creating. His was only a conglomeration of huts and data. It was the living mass of individual men and women, with their families back home, that made it what it was; the human mass that gave it its existence, the movement of men through its gates, that was to give it its measureless reality ad infinitum over these years and, continued into the second phase of its existence in which I was to share its life and in the years since, the lives of many more who have passed through its gates.

A UNIQUE NICHE IN NAVAL HISTORY

From this point in time forty years on it can be seen that HMS Collingwood has indeed a claim to a place in the watershed of naval history. It saw the end of an era when the Hostilities Only Seaman Entry ended and the Establishment was taken over by the new and developing Electrical Branch, t become the nerve centre of the modern Navy we now know it.

The old ways and methods of naval training in gunnery and navigation, communications and seamanship, came under the impact of modern science. We were already aware of the change in the growing tensions between the West and East sections of the establishment as the grip of the electronics ‘take-over’ invaded the four seamanship areas.

The quarterdeck gunnery classrooms were allocated as Chapels and common rooms for the Catholic and Church of Scotland and Free Churches personnel. This was done to return the Warrant Officers Wardroom to its original use as accommodation for junior officers. Father Costello and I had previous dealings with Mr Morton the Area Dockyard official in charge of properties and he was most helpful; he fitted out our two Chapels to our every wish. I remember it was a source of wonder to the other chaplains when we exchanged the prayer rails we had; his dark teak one for my light oak one; a sensible practical exchange to suit the rest of furnishings and in keeping with my Communion Table.

A week or two after he had settled in his new Chapel Gerald was drafted to Marine Commandos. His classes had come to an end. It was the first break in our very close friendship. We met again for three short hours on the Sunday before D Day. He was sitting in my office at Collingwood waiting for me to come in from church. The General had dropped him there on his way to the final briefing at Southwick House. Gerald was to obtain a radio for the men. The Commandos had moved into canvas in the small hours of the morning, they were in the wood a mile west of Hambledon Bridge. I got him the radio and took him home to lunch. When his time was up I asked him for his location and he had not a clue, he knew vaguely that it was somewhere west. He was lucky that I had been using the roads through the Top Security camp in the recent period when the fall in workload at Collingwood had given me more time for the extension of my oversight and I was able to visit the crews of landing craft in the little havens and rivers of the New Forest sea board. I had been doing this task since their inception, visiting the headquarters of Captain Hughes-Hallet at Cowes on a weekly basis.

I can recall clearly the excited exclamation of recognition as we crossed the bridge at Hambledon when Gerald said ‘I remember that gun post’ and when we entered the woods past the American sentry who knew me, we had hardly gone a mile amongst the hundred of tents when he said ‘Oh! There is my tent’. How he picked it out I shall never know.

That night he went in with the first wave of assault on the beaches opposite Caen. I heard that they had terrible casualties. The next night I was on duty with the assault ships bringing back the wounded. I kept on seeking news of him. On the Friday night I heard that an RC Chaplain, a Commando, was on board badly wounded. I went to see him but it was not Gerald. Three years later we were serving together again in HMS Raleigh and I went with him to meet a new padre who had changed from the Army to the Navy. It was the Commando I had seen badly wounded. He remembered and recognised me. He was Padre Bill Brisco.

Gerald and I served together until his demobilisation and he returned to his work within the Redemptorist Order. In 1952 when I was serving in HMS Daedalus, our RC Chaplain Michael Barry, was taken fatally ill and I was asked by Commodore McCarthy to arrange for their Sunday services. I phoned the Redemptorist House at Streatham, London and got Father Costello to fill in. He came and he lived in our home for three weeks, cementing a friendship that has continued across the years. Strangely enough, when he went and a new chaplain was appointed, it was Bill Brisco who turned up to take the lace of Michael Barry.

To get back to Collingwood. The takeover went on a pace. The Royal Marines had taken over the maintop enclosed shelter and gymnasium for stores and workshops. The foretop became the Marine transport area where Monrad vans were equipped and overhauled on a weekly basis for the shuttle service to the battlefields of Europe. All this had taken place before Admiral Sedgwick had handed over to Captain Benson on 31st August 1944, when the final break with seamanship and gunnery traditions had taken place.

The longboats on their davots, the capstain and chain lockers etc and the large gunnery building fell into disuse, until in 1945 it became the rehabilitation centre for men retaining for discharge to civilian life.

So the bell bottomed Jack gave way to the fore and aft rigged Artificer and lecture rooms began to fill with all the electronic equipment of the new age of technological science. I saw it all happen.

My Collingwood flimsies read like the passing out parade of commanding officers from Sedgwick to Benson to Keble-Wight. It was a period of swift change to which the old hands found it hard to adjust. The old routine gave way to the new the old faces began to disappear from the Wardroom and the CPO’s Messes. Soon Mr Brown and Mr Ward, the Officers of the Watch, the Barrack Master and I were the last of the originals. Every week new faces arrived in the wardroom – HO specialist officers, university graduates and specialists in electronics with the intellectual capacity to master the continually expanding horizons of radar and electronic development. They were men of undoubted ability who had jumped rank because of their specialisation and some of them were lacking in the naval disciplinary requirements of a training establishment. They were a grand lot of fellows. Some of them with all the athletic fervour of overgrown students, which indeed they were. They were still students continuing hard in their studies.

I remember the day the document was passed round the Wardroom offering permanent service in this new Branch which was to become the foundation stone of the modern Navy.

Many signed the roster but there were others whose names were missing from it. They were being pressed to reconsider the opportunity offered. One of them I remember was the son of the Manse in my northland. He was a brilliant student, senior to me in the Honours Mental Philosophy Degree course at Edinburgh University 20 years before. He was a magnificent specimen of a red headed Scot, a Rugby and rowing Blue and as wild and untamed as the Pentland Firth on whose bleak shore he has been born and bred. He was a full-blown Commander ‘Wavy Navy’ but its discipline was not for his untamed spirit. When he left the service he seemed to flit around the civil airfields in England and Scotland. I used to ask about him until I heard he had joined the Dounray Nuclear Establishment, then in its infancy and he was there until he retired in recent years. He was in some kind of responsible personnel post. In a unique way he was continuing in his father’s footsteps, to be responsible for the inhabitants of the parish of Reay for indeed that is where the nuclear station is built. His father had been there for well over 50 years; he ruled with a stern Calvinism and with a broadminded humanity that made him feared and loved. There was a story told in my youth, how the minister of Reay, at the catechising of his parish, was seen at the top of the village street and the good man of the house near the bottom was sent to the village pub to fetch the refreshment. He came home ahead of the minister inebriated. The good wife, so ashamed, pushed him in the box bed and closed doors. The minister arrived and the catechising began. ‘Now’ said the minister, ‘Tell me about Adam’s fall’. The good woman got up, opened the bed doors and called ‘Come out of there Adam, you should be ashamed of yourself, the minister has head all about you’ and of course he had. He was reputed to have a dry sense of humour and would not have passed up such an opportunity.

I am sure it was his peculiarly dry sense of humour passed onto Donald that instigated the scrum attack on the Bomb Blast Safety Wall outside the Wardroom Door, in order to celebrate the fall of Hitler on VE night. After dinner, in full Mess Undress, they formed a formidable scrum, pushed and pushed until they fell on a crumbled heap of bricks. The Commander, who shall be nameless, ‘was not amused’. He shared not their sense of humour. Their leave stopped, messages had to be sent to waiting wives that their men folk would not be home that night or the next maybe, until the unknown culprits appeared before the Commander.

Perhaps it was my extrovert sense of humour that saw the funny side of the whole incident, from the discomfiture of the Executive to the stoppage of leave to ‘Officers and Gentlemen’. Had I not been missing, my fourteen stone would have been press-ganged into such a sublimating expression of sheer freedom of mind and spirit which overcame the whole nation on that memorable night.

This would seem to be a fitting end to the Collingwood wartime story. If I have glossed over the grim reality of war, it is because even now after forty years, it is difficult to write of the many sorrows and grim anxieties that loomed up week after week in the Chaplain’s office. In these early days of war there was no welfare department where the trained visitors do their marvellous work, only the Chaplain. Our telephones were red hot, passing on men’s concern after news of blitz came across the radio. We became adept at tracking up necessary information. In small towns the police never let us down. After 10 years of city crunch experience I knew where to begin in a city. It never failed, to ask to be put through to the Mayor or the Provost, for prompt action. The night of the terrible blitz on Liverpool, when Birkenhead dockyard area was specially mentioned on the News, four young fellows crowded into my office in sore stress, their homes were actually on the dock front. I phoned the Council Offices, gave names and addresses and within minutes the news came. Their homes were completely wrecked but their families were safe in a Church Hall. We had them put on the first train with transport to the ferry within the hour. Just one incident out of many more.

I have used this story because it illustrates the feedback of the work of the Chaplain in peacetime as in war. In 1953 on the dockside at Liverpool, a porter was helping me to get my wife and her baby son and young daughter out of a taxi when a shout came from thirty or forty yards down ‘Leave the Padre to me, come and take over here’. An orange coated porter rushed up, his face beaming and said ‘You don’t remember me Sir but I shall never forget you. You stay here and I will see your wife and family on board and come back for you and the gear’. Three years later we docked at 7.30 in the evening and a porter was standing on the dockside, in his off-duty suit, waving to catch our attention. He was first up the gangway. He had been watching the passenger list for the previous six months, waiting for our return. We were first off the ship at 7am. Our gear was already freed from Customs and the family’s car was standing by for us to get away. He was on standing by for us to get away. He was one of those lads. ‘Cast thy bread on the waters’ so say the Good Book.

I would finish where I began. I have kept two tributes as a fitting conclusion. I make tribute to the Wrens. They were the light and life of every department from the cookhouses and stores to the offices of the executive and the busy hive of the ship’s office. They were not only an adornment they were the backbone of the Establishment. The very atmosphere of it seemed to have got into their system. They were cheerful, willing workers. The messengers who popped in at the office, as regular as the bugle calls, lightened up the days for us. The Pay Office was bossed by the CPO and PO, two Wrens who themselves worked long after hours, nights on end, keeping the thousands of entries up to date. The First Officer, Millicent Fry, was the daughter of the famous CB Fry. She was a young lady of great charm who knew how to weedle and get things done. We saw their numbers grow from the first thirty entries to over nine hundred strong. They were not housed in the Establishment. Between the Training Commander’s Office and the Dental Department, they had a Common Room and Rest Room with small dormitory accommodation for duty staff. Most of them were local girls who lived at home.

The National Childrens Home in Alvestoke was taken over as Wrens’ quarters. I remember the first time my sister-in-law, the PO Pay Wren came home, with her affronted complaint that she had been put in charge of the small children’s wing, where the seating accommodation in the bathroom was not only too near the floor and in a line, but also as Mark Twin once said ‘Exceeding small’.

My last tribute I would begin with the words, ‘The first shall be last and the last first.’

I doubt whether anyone has remembered or indeed known that the first batch to enter the Establishment were not ‘Hostilities only’ but seventeen year old recruits for ‘Seven and Five’ (years). Their ship’s book number began PSSX. They formed a new and select Branch ‘Defence Equipped Merchant Ships’ – The DEMS. They were being trained for a dangerous task. They were at the beginning of the Gunnery Course when I arrived and my first caller at 4.30 on my first Monday in the Establishment was a lad who was utterly miserable and homesick. He had run away from home. He had left a widowed mother with four of a family and the realisations of its consequences had begun to dawn on him. He was shy and introvert and I was at a loss how to deal with him so I took him home. It was a favourite trick of mine; waifs and strays were always to be found there and I knew he would get a warm welcome from my wife and sister-in-law, the Pay Wren.

When we arrived the young Australian Chaplain from HMS Daedalus, the Revd Peter Parker was with them. He had been invited to a farewell dinner he was on draft to HMS Prince of Wales. His name is now amongst their honoured list of dead. It was a slap up dinner to fit the occasion, and the lad was too embarrassed to eat. However, he came back the following week and from then on he became a fixture in our home. The DEMS as they were called were drafted RNB then to Northern Parade School, Portsmouth; from there latterly to Totton. They were the heroes in top mould, climbing on board coastal steamers, tankers, etc their light aircraft gun over their shoulder off the Isle of Wight or Portland or Southampton, to take over the night run through the Straits of Dover. They went through during the dark hours to Southend. There they handed over to the Army for the North Sea stretch, then back on the night run with the southbound convoy. In eighteen months the three hundred and fifty Collingwood Batch dwindled, until there was little more than thirty odd left. ‘Out Willie’ was a survivor three times in the month of May 1941. It was a trauma for a teenager. He went home on 5th May for his first seven days survivors leave. He had lost four of his mates during the night, the ship sinking under him as he and another tried to break open the jammed Bridge door, where two of them were with the Captain. The neighbours, in his Parkhead Glasgow street feted him. He was back within the week on his second survivor’s leave of twelve days and they did not believe him. In his typical Galsgow humour he said they event sent the ‘Bobbie’ to see if he was adrift. He returned and picked up a convoy off Plymouth. That night they were bombed and he was launched into a sea of oil from off a stricken tanker. When he was offered another spell of leave he refused it, telling his story and ending with the remark ‘If I go home this time they’ll chase me down the street’. The Commander at Northern Parade got in touch with me and he was sent home to us.

I think you will agree this is a fitting end to the Collingwood wartime story. I have always thought that these seventeen year olds were the epitome of the silent service to which they were proud to belong, the unsung heroes of the war. They deserve a place in this inadequate tribute. They epitomise the honoured place, HMS Collingwood, the ships company and trainees will always hold in the annals of naval history.

This completes the Rev's history of Collingwood and I thank him.

They really were like this:-

The Demise of Jack Tar

The traditional male sailor was not defined by his looks. He was defined by his attitude; his name was Jack Tar.

He was a happy go lucky sort of a bloke; he took the good times with the bad.

He didn't cry victimisation, bastardisation, discrimination or for his mum when things didn't go his way.

He took responsibility for his own, sometimes, self-destructive actions.

He loved a laugh at anything or anybody. Rank, gender, race, creed or behaviour, it didn't matter Jack would take the piss out of anyone, including himself. If someone took it out of him he didn't get offended it was a natural part of life. If he offended someone else, so be it.

Free from many of the rules of polite society, Jacks manners were somewhat rough. His ability to swear was legendary.

He would stand up for his mates. Jack was extravagant with his support to those he thought needed it. He may have been right or wrong, but that didn't matter. Jacks mate was one of the luckiest people alive.

Jack loved women. He loved to chase them to the ends of the earth and sometimes he even caught one. (Less often than he would have you believe though) His tales of the chase and its conclusion win or lose the stuff of legends.

Jack's favourite drink was beer, and he could drink it like a fish. His actions when inebriated would, on occasion, land him in trouble. But, he took it on the chin, did his punishment and then went and did it all again.

Jack loved his job. He took an immense pride in what he did. His radar was always the best in the fleet. His engines always worked better than anyone else's. His eyes could spot a contact before anyone else's and shoot at it first. It was a matter of personal pride. Jack was the consummate professional when he was at work and sober.

He was a bit like a mischievous child. He had a gleam in his eye and a larger than life outlook.

He was as rough as guts. You had to be pig headed and thick skinned to survive. He worked hard and played hard. His masters tut-tutted at some of his more exuberant expressions of joie de vivre, and the occasional bout of number 9' s or stoppage let him know where his limits were.

The late 20th Century and on, has seen the demise of Jack. The workplace no longer echoes with ribald comment and bawdy tales. Someone is sure to take offence. Where as, those stories of daring do and ingenuity in the face of adversity, usually whilst pissed, lack the audacity of the past

A wicked sense of humour is now a liability, rather than a necessity. Jack has been socially engineered out of existence. What was once normal is now offensive. Denting someone else's over inflated opinion often of their own self worth is now a crime.

And so a culture dies...

This is a money saving card for service and ex service personnel.

Just contact the site and follow the instructions.

Most of the shops are the high street 'giants'.

Just contact the site and follow the instructions.

Most of the shops are the high street 'giants'.

Missing the_Royal Navy?

Here's how to recapture the atmosphere of the good old days & simulate living onboard ship once more !

15 Devise menus for your family a week in advance without looking in the larder or fridge.

16 Set your alarm clock to go off at random times through out the night, when it goes off, leap out of bed, get dressed as fast as you can and then run into the garden and break out the garden hose.

17 Once a month, take every major household appliance completely apart then reassemble.

18 Use four spoons of coffee per cup, and allow to sit for three hours before drinking.

19 Invite about 85 people who you don't like to come and stay for a month.

20 Install a small fluorescent light under your coffee table then lie underneath it to read books.

21 Raise the threshold and lower the top sills of all the doors in your house. Now you will always either hit your head or skin your shins when passing through them.

22 When baking cakes, prop up one side of the tin whilst it is in the oven. When it has cooled spread icing really thickly on one side to level it out again

23 Every so often, throw your cat in the bath and shout, "man overboard". Then run into the kitchen and sweep all the dishes and pans onto the floor whilst yelling at your wife for not having secured for sea

24 Put on the headphones of your stereo, do not plug them in. Go and stand in front of the dishwasher. Say to nobody in particular, "dishwasher manned and ready Sir". Stand there for three or four hours. Say once, again to nobody in particular,"dishwasher secured". Remove the headphones, roll up the cord and put them away

25 Nickname your favourite shoes "steamies", then get your children to hide them around the house on a random basis.

Here's how to recapture the atmosphere of the good old days & simulate living onboard ship once more !

- Build a shelf in the top of your wardrobe and sleep on it inside a small sleeping bag

- Remove the wardrobe door and replace it with a curtain that's too small

- Wash your underwear every night in a bucket, then hang it over the water pipes to dry

- Four hours after you go to bed, have your wife whip open the curtain, shire a torch in your eyes and say, "Sorry Mate".

- Renovate your bathroom. Build a wall across the centre of your bath and move the shower head to chest level. Store beer barrels in the shower enclosure.

- When you shower, remember to turn the water off while you soap

- Every time there is a thunderstorm, sit in a wobbly rocking chair and rock as hard as you can until you are sick ! !

- Put oil instead of water into a humidifier and then set it to high.

- Don't watch TV, except for movies in the middle of the night. For added realism, have your family vote for which movie they want to see, then select a different one.

- Leave a lawnmower running in your living room 24 hours a day to re-create the proper noise levels. (Mandatory for engineers)

- Have a paper-boy cut your hair.

- Once a week blow compressed air up through your chimney. Ensure that the wind carries the soot over onto your neighbour’s house. When he complains, laugh at him

- Buy a rubbish compactor, and use it once per week. Store up your rubbish in the other side of the bath.

15 Devise menus for your family a week in advance without looking in the larder or fridge.

16 Set your alarm clock to go off at random times through out the night, when it goes off, leap out of bed, get dressed as fast as you can and then run into the garden and break out the garden hose.

17 Once a month, take every major household appliance completely apart then reassemble.

18 Use four spoons of coffee per cup, and allow to sit for three hours before drinking.

19 Invite about 85 people who you don't like to come and stay for a month.

20 Install a small fluorescent light under your coffee table then lie underneath it to read books.

21 Raise the threshold and lower the top sills of all the doors in your house. Now you will always either hit your head or skin your shins when passing through them.

22 When baking cakes, prop up one side of the tin whilst it is in the oven. When it has cooled spread icing really thickly on one side to level it out again

23 Every so often, throw your cat in the bath and shout, "man overboard". Then run into the kitchen and sweep all the dishes and pans onto the floor whilst yelling at your wife for not having secured for sea

24 Put on the headphones of your stereo, do not plug them in. Go and stand in front of the dishwasher. Say to nobody in particular, "dishwasher manned and ready Sir". Stand there for three or four hours. Say once, again to nobody in particular,"dishwasher secured". Remove the headphones, roll up the cord and put them away

25 Nickname your favourite shoes "steamies", then get your children to hide them around the house on a random basis.

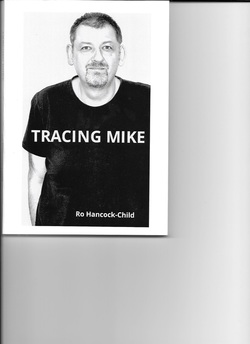

Can you help me please?

This is the question we get most of on the email side or letters.

They are usually from relatives trying to trace fathers,grandfathers uncles etc.

Most find a photo and try from there.

Ken and Mike know more about it on our Association side.

Indeed, Mike sent me this book to look at and he 'stars' in it on pages 92 to 100.

This is the story of the search for the father of the author , Ro Hancock-Child's, husband who was called Mike.

She was helped in no small way by our 'Mike' who managed to point her in the right direction and considering they had the wrong surname !!!!

I was going to copy the pages but suddenly thought of copy write as the author is still alive ( according to Google). Should you wish to read it, I'm sure you could get a copy from your library, or I'm returning this to Mike at the next AGM and he may loan it out!

This is the question we get most of on the email side or letters.

They are usually from relatives trying to trace fathers,grandfathers uncles etc.

Most find a photo and try from there.

Ken and Mike know more about it on our Association side.

Indeed, Mike sent me this book to look at and he 'stars' in it on pages 92 to 100.

This is the story of the search for the father of the author , Ro Hancock-Child's, husband who was called Mike.

She was helped in no small way by our 'Mike' who managed to point her in the right direction and considering they had the wrong surname !!!!

I was going to copy the pages but suddenly thought of copy write as the author is still alive ( according to Google). Should you wish to read it, I'm sure you could get a copy from your library, or I'm returning this to Mike at the next AGM and he may loan it out!

Message from our Treasurer

Hello Shipmates, once again it is coming up to subscription time. Subs are £7.00 and are due on 2nd January they can be paid by standing order, form to be completed signed and taken/sent to your bank or building society if you haven't already completed one. Other methods of payment are by bank transfer or internet banking and made payable to bank account number 30 97 42 00704704. You may also send a cheque/postal order direct to me made out to HMS Collingwood Association at the address below. If you are sending your station card to be up dated please enclose a stamped addressed envelope.

Any queries I can be contacted by email on [email protected] or by calling 0191 2584694.

Hello Shipmates, once again it is coming up to subscription time. Subs are £7.00 and are due on 2nd January they can be paid by standing order, form to be completed signed and taken/sent to your bank or building society if you haven't already completed one. Other methods of payment are by bank transfer or internet banking and made payable to bank account number 30 97 42 00704704. You may also send a cheque/postal order direct to me made out to HMS Collingwood Association at the address below. If you are sending your station card to be up dated please enclose a stamped addressed envelope.

Any queries I can be contacted by email on [email protected] or by calling 0191 2584694.

To finish - here is a couple of 'funnies'

http://safeshare.tv/w/ZXQqOdKCMp

NO ENGLISH TRANSLATION NEEDED .

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

In an Underground station in London.

There were protesters on the concourse handing out pamphlets on the evils of Britain .

An elderly woman was getting off the escalator and a young (20-ish) female protester offered her a pamphlet, which she politely declined. The young protester put her hand on the woman's shoulder (as a gesture of friendship?) and in a very soft voice said, 'Madam, don't you care about the children of Iraq ?'

The elderly woman looked up at her and said, 'My dear, my father died in France during World War II, I lost my husband in Korea and my grandson in Afghanistan . All three died so you could have the right to stand here and badmouth our country. If you touch me again, I'll stick this umbrella up you’re a*se and open it.'

God Bless Older Generation.

______________________________________________________________________________________

https://www.youtube.com/embed/HUgv5MDF0cQ

________________________________________________________________________________

An elderly couple had just learned how to send text messages on their mobile phones. The wife was a romantic type and the husband was

more of a no-nonsense guy.

One afternoon the wife went out to meet a friend for lunch, after a couple of glasses of wine she decided to send her husband a romantic text message and she wrote: "If you are sleeping, send me your dreams. If you are laughing, send me your smile. If you are eating, send me a bite. If you are drinking, send me a sip. If you are crying, send me your tears. I love you."

The husband texted back to her: "I'm on the toilet. Please advise."

-----

That's all for this one. Next edition in the Spring of 2016.

Have a great Christmas and Happy and Healthy New Year.